60/40 and other dinosaurs

A simple practical step to take your portfolio from the 1990s into the 2020s...

Over decades, investors’ ideas about how to build the perfect portfolio have evolved. Large pension fund investors typically led innovation, with consultants and smaller pension funds following; then discretionary wealth managers followed by retail investors as trends trickled down.

Markowitz is the architect of modern portfolio theory, which investors have worked with and adapted over time. In the 1970s, with high interest rates available, institutional and pension investors focussed on fixed income. In the 1980s many turned to domestic equities, and the 60/40 equity and bond split within portfolios became common. The 1990s saw further diversification, and international equity investing became mainstream. This century, institutions have further diversified portfolios, adding alternative asset classes such as private equity, hedge funds, real estate, and illiquid assets.

Through the looking glass

The investment trust sector has in some ways echoed these developments. In the ‘80s and ‘90s trusts were launched to capitalise on ‘new markets’ such as Europe, Asia and Emerging Markets, with institutions enthusiastic supporters. Similarly, the booming listed hedge fund sector in the mid-2000’s came on the back of the experience institutional investors had of Cayman based hedge funds in the late ‘90s and early 2000’s. Trusts continue to launch, enabling investors to harness hard-to-access asset classes, often illiquid, but offering potential to diversify traditional equity and bond risks.

Will the future continue to echo the past?

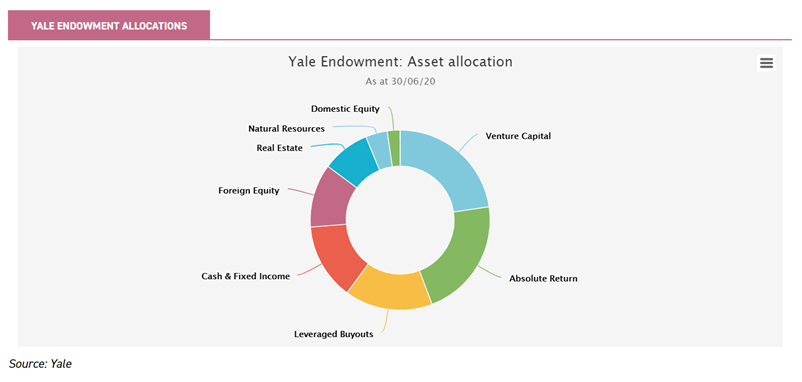

The recent death of David Swenson, a pioneer in evolving institutional portfolios, caused us to examine what the future might be for discretionary wealth manager or retail investor portfolios, assuming the future continues to echo the past. David ran Yale Endowment from 1985 until he died in May 2021 delivering strong and consistent returns. He revolutionised Yale by applying an extension of Markowitz’s theory. He identified eight asset classes, with weightings determined by risk-adjusted returns and correlations. A diversified strategic asset allocation was made to the asset classes with regular rebalancing (which some researchers believe contributed 40% of Yale’s excess returns), and a dedicated manager selection team.

Lessons from Yale

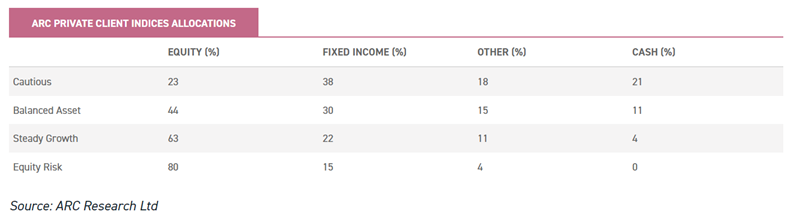

So far, so not very different (in theory at least); we believe the key lessons from Swenson and Yale are their very different attitudes to equity risk (high tolerance), and willingness to embrace private markets and illiquidity. Their ultra-long term/perpetual investment mandate helps embrace risk and illiquidity. Many private client, JISA or SIPP portfolios also have multi-decade investment horizons but the differences between Yale’s current portfolio and the various ARC Private Client Indices are stark. Notable in the latest ‘model’ allocations from ARC is the significant cash and fixed income exposures – even for those with the highest risk.

Overall, Yale’s exposure to equity is roughly similar as the ‘equity risk’ allocation of private client portfolios; the real difference is where Yale gets its equity exposure. This chart shows Yale’s very high exposures to Venture Capital, Absolute Return and Leveraged Buyouts (60% of exposure) - perhaps ten times the exposure that private client or retail portfolios typically have.

Follower of fashion

Yale’s success prompted many smaller endowments to follow its example by adopting a similar asset allocation. Swenson regularly warned against a blanket application of the model, and the results of smaller endowments that adopted Yale’s model have generally been mediocre. Why Yale has maintained its performance lead remains hard to pin down; most explanations centre around having first mover advantage (with many managers now closed to new investors), the resource and skill the Yale team bring to manager selection, and the practical difficulties of putting capital to work in less liquid, private markets.

We don’t believe the reasons given for underperformance apply to a retail investor; investment trusts are by definition pretty much closed to new investment. The secondary market is the entry point, so for small investors, all trusts are open for business during LSE trading hours for subscriptions and redemptions. Manager selection is a significant hurdle to achieving returns as strong as Yale’s but we believe the investment trust universe represents a ‘premier league’ for investment management talent.

Firstly, there are a limited number of trusts, so demonstrable skill is required to be awarded a mandate. Secondly, an independent board continually monitors performance, taking action if it is not maintained. Thirdly, the trust structure gives managers a higher chance of performing to the best of their ability away from the pressures of inflows and redemptions and liquidity concerns of underlying stocks. We contend that the investment trust universe provides a good source of talent to populate a long term, Yale model allocation.

Using investment trusts to take the Yale road

An analysis of the long term returns from Yale’s asset class buckets and those of listed funds show that broadly similar returns are achievable. Investors with long investment horizons, such as SIPPs or JISAs could adopt Yale’s more adventurous asset allocation framework; the challenge is accepting the risk and illiquidity that comes with private markets investments.

This change for SIPP investors is dramatic, but no more so than the changes made by Yale itself in the 1990s. In 1990, 65% of Yale Endowment was U.S. stocks and bonds. Today, target allocations are 9.75% in US securities and cash, with diversifying assets of foreign equity, absolute return, real estate, natural resources, leveraged buyouts and venture capital representing 90% of the portfolio.

Will investors follow and take the plunge? We believe Yale’s strong performance over the years justifies it and, if history is anything to go by, many investment portfolios will become less dominated by listed equities. We already see a trend towards private market investments, but Yale suggests the trend has a long way to go.

Investment trusts deliver an advantage, with a wide selection of strategies and managers available giving a relatively liquid way of gaining exposure to Yale’s ‘non-traditional asset classes’ where the ‘endowment’s long-time horizon is well suited to exploit illiquid, less efficient markets’. SIPP investors with a multi-decade investment horizon could adopt an ‘endowment’ portfolio model.

Several of Yale’s buckets are relatively simple to populate from the open-end or investment trust sectors, including domestic equities, foreign equities, cash and bonds, real estate and natural resources. Those seeking suitable absolute return funds might consider BH Macro, some constituents of the AIC Flexible sector or a plethora of absolute return UCITs funds.

Several of Yale’s buckets are relatively simple to populate from the open-end or investment trust sectors, including domestic equities, foreign equities, cash and bonds, real estate and natural resources. Those seeking suitable absolute return funds might consider BH Macro, some constituents of the AIC Flexible sector or a plethora of absolute return UCITs funds.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

Yale’s real differentiator is its 35% target allocation to venture capital (VC) and leveraged buyouts, but there are relatively few directly comparable avenues for the VC allocation, which Yale targets as 23.5% of its portfolio. Yale’s venture managers target innovative start-ups which is undeniably a high-risk strategy – it expects long term real returns of 12.3% pa but with risk of 37.8%.

Over 20 years, Yale has achieved 11.2% pa from its portfolio, a little disappointing given the risks. The AIC’s Growth Capital sector is an obvious avenue to explore, but remember trusts in this area have relatively short track records and it takes time for managers to see the fruits of their labour. Trusts offering exposure to venture include Third Point Investors (TPOU) where the board recently approved increased allocation to venture and private equity up to 20% of NAV; it is developing a strong track record in the venture space, with the IPO of one investment, SentinelOne, achieving a first day trading valuation of more than 100 times the price at which Third Point invested in 2015, illustrating the potentially explosive returns achievable. AI-driven lender Upstart is a second high profile IPO from its portfolio which has appreciated more than five times since December 2020.

Venture is a differentiated strategy to private equity, but HarbourVest Global Private Equity (HVPE) has the highest allocation of listed private equity trusts, with 35% of NAV in ‘venture and growth equity’ funds; other trusts with exposure to VC include RIT Capital Partners (8.9%) and Scottish Mortgage.

Buyouts

Yale’s leveraged buyout allocation is a similar strategy to the listed private equity (LPE) sector, with a wide range of approaches to access ‘extremely attractive long-term risk-adjusted returns’ from a strategy that ‘exploit[s] market inefficiencies’.

We believe buyouts represent a lower risk proposition than venture and different in that buyout managers control their companies, set strategy, drive value creation and decide when to crystallise value by selling. Yale’s buyout portfolio expects real returns of 8.6% with risk of 21.1%, and delivered 11.2% p.a. over 20 years. The LPE sector can offer better access than Yale has, as investors can buy into funds with established portfolios of investments, with most trusts trading at material discounts to NAV.

First steps in a move towards Yale

Confirming the attraction of private equity, the venerable F&C Investment Trust has long had a commitment to it as part of its global investment approach, now near 10% of NAV. Investors wishing to move towards an endowment model might consider being even bolder, allocating 20% of their portfolio into LPE trusts rather than equity exposure elsewhere - a significant divergence from traditional portfolios with between zero and 5% in LPE trusts.

The LPE sector offers a wide range of approaches and slants, so investors can diversify their exposure to managers, sectors and style. This table splits the universe by the way each trust invests. Direct trusts have a single management group making investments, with concentrated portfolios that expose investors to higher specific risk and potentially higher rewards. By contrast the highly diversified fund of funds have underlying exposure to many thousands of private companies. Between these two poles, some trusts have more concentrated portfolios, but relatively little specific risk to individual companies; investors can choose based on risk appetites, sector preferences and premiums/discounts to NAVs.

LPE sector trusts provide a wide range of different exposures, all in the same broad area of private equity investing. They will be subject to the broad market sentiment driving premiums and discounts; with many complementary attributes, investors can to build diversified exposure.

ICG Enterprise (ICGT) offers a hybrid approach to PE investing. 52% of the portfolio is through third party funds and 48% within the ‘high-conviction’ portfolio where ICG has directly selected underlying companies through co-investments and ICG funds. This has delivered consistently strong value for shareholders, with ICGT on track to deliver its 13th consecutive financial year of double-digit portfolio growth.

NB Private Equity Partners (NBPE) has a unique approach within the London LPE sector, focussing on equity co-investments - equity investments made alongside third party private equity sponsors have generated strong returns. NBPE has a wide spread of investments across sectors, companies, and PE managers – including 64 core investment positions (greater than $5m) made alongside 38 different PE sponsors (31/03/2021). Investing directly means NBPE’s investors only pay one layer of management and incentive fees. With the portfolio looking increasingly mature, the momentum behind realisation activity seen over recent months could continue.

BMO Private Equity (BPET) offers a distinctive approach to PE, investing with managers at an early stage; its manager believes this means exposure to more motivated teams and to lower mid-market deals where BMO is more likely to be offered co-investment opportunities. We expect the level of co-investments to remain between a third and a half of NAV, a rise in the number of opportunities that BPET’s managers have observed in this area over the years.

As part of a diversified portfolio, the higher returns generated by directly invested private equity trusts can be attractive, notwithstanding the greater volatility of returns. HgCapital has a well-established track record as a directly invested private equity trust, specialising in software and business services in Europe. The trust has delivered strong long term returns, perhaps the reason its shares currently trade at a premium.

Many of the same dynamics have benefitted Oakley Capital Investments (OCI), which focuses on companies in the European technology, education and consumer sectors. Digital disruption and the opportunities it presents is a recurring theme in OCI’s portfolio. This placed OCI well at the beginning of 2020, and portfolio companies have been nimble in adapting to the digital opportunities presented by lockdown. Entrepreneurial founders of businesses represent a key part of Oakley Capital’s DNA, with a track record of being the first institutional investors in growing companies. The Oakley network is key in helping the team access compelling investments at attractive valuations at a time when competition is strong. OCI’s strong balance sheet is also a differentiator, having gone into the market sell-off with net cash of 36% of estimated net assets. This put the trust in a strong position, and Oakley Capital has made a number of interesting investments since then. Cash now represents c. 22% of estimated NAV.

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Read the latest edition of DIY Investor Magazine

DIY Investor Magazine

The views and opinions expressed by the author, DIY Investor Magazine or associated third parties may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected by EQi.

The content in DIY Investor Magazine is non-partisan and we receive no commissions or incentives from anything featured in the magazine.

The value of investments can fall as well as rise and any income from them is not guaranteed and you may get back less than you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

DIY Investor Magazine delivers education and information, it does not offer advice. Copyright© DIY Investor (2016) Ltd, Registered in England and Wales. No. 9978366 Registered office: Mill Barn, Mill Lane, Chiddingstone, Kent TN8 7AA.