Investing basics: how to pick the right fund 'share class'

One of the least concerns a fund investor should have is that of a lack of choice – writes Tabitha James of DIY Investor Magazine

In fact, starting out as a funds investor can be a bewildering, if not somewhat overwhelming business; at the last count, there were more than 8,000 funds registered for sale to UK investors.

Creating a balanced portfolio, or collection of funds, suitable for your appetite for risk, investment objectives and overall view of the world can be very personal and require a bit of elbow grease.

In common with a number of retail brokers and ‘fund supermarkets’ EQi has a fund selector tool that allows you to filter down this unwieldy number of options based upon a range of criteria.

The ‘big picture’ selectors allow you to select whether you are seeking income or growth; you can select by IMA sector – e.g. UK Equity Income/Global Emerging Markets; you can select by target yield, geographical and industry sector, the underlying asset class the fund invests in, and the analysts’ view.

See EQi's Mutual Funds Selector here

By applying these filters you will start to hone down the options that are right for you; however in this latest Investment Basics piece we are going to look at something that is perhaps less obvious and less well understood – the different ‘share classes’ that can exist in a single fund.

Funds often come in at least six variants and buying the wrong one could mean that you are overpaying every year; here is how to identify the ‘best’ share class.

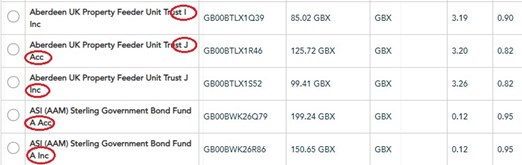

Once you have applied the filters described above, you may find that there appear to be numerous versions of a particular fund.

Navigating these can be a challenge as funds develop different ‘share classes’, often designated by a different prefix or letter; this could be ‘inc’ or ‘acc’ or even more bewilderingly, ‘I’, ‘Z’ or ‘R’.

Choosing the right version at the outset can be complex but vitally important because if you put money into the wrong one you could find yourself paying unnecessary charges each year and potentially facing the cost and inconvenience of switching to the correct one later.

Even seemingly small differences in annual fees can make a big difference to the eventual value of your pot if returns are compounded over many years or decades.

Why are there so many versions of funds?

The first distinction, and possibly the most useful, is the way in which the fund treats its profits and whether the investor is seeking regular income – where profits are returned to the investor – or long term capital growth – where profits are retained within the fund to facilitate further growth.

Income units are normally designated ‘inc’ and those for reinvestment, also called ‘accumulation’, are abbreviated to ‘acc’.

Whilst inc/acc may be relatively straightforward, the reasons for other versions of the fund can be a little more difficult to fathom.

Most other share classes relate to different annual charges; for example, large corporate investors such as pension schemes pay less to invest in funds so they qualify for an ‘institutional’ or ‘I’ share class (sometimes with a minimum investment of £1m), while DIY investors have to satisfy themselves with the ‘retail’ class, often abbreviated to ‘R’ (with investments from £50).

‘Retail’ share classes traditionally included a commission that could be passed on to financial advisers or the fund shop, raising the potential for advisers to recommend a fund that they earned the most commission on rather than the best one for the client’s needs; this practice has now been outlawed and advisers have to charge transparent and pre-agreed fees instead.

This change led to the need for more versions of a particular fund – share classes – that do not include commissions and are therefore cheaper.

The versions of a fund that have been stripped of commissions are called ‘clean share classes’; there, as a minimum, you can expect to find four types of each fund – retail accumulation, clean accumulation, retail income and clean income.

However, that not the end of it, because some fund shops have negotiated special reduced fees on certain funds because of their potentially large buying power; these deals require their own share classes, sometimes called ‘super-clean’.

Yet more types can be created if a fund is available in different currencies or for a range of other reasons including one-off versions for particular institutional clients.

Most ordinary investors will want to decide between income and accumulation and then identify the clean (or super-clean) share class; however, that’s still not the end of it.

There are other letters in use that may have different meanings according to the fund that’s using them; the most common ones are A, B, C, P, T, Y and Z, with each one denoting different levels of charges or ways that you can buy into the fund. Eg:

- ‘A shares’ may only be available to direct investors – ie those that contact the investment company direct and invest without going through an IFA or a platform. These may have a minimum investment level.

- ‘C shares’ may only be available via independent financial advisers or platforms.

- ‘X shares’ may be old style shares that carried an exit charge; they are no longer available to new investors, but if you’ve already invested in a fund by buying this class you may continue to invest in them.

- ‘Y shares’ may only be available through investment platforms.

- ‘Z shares’ may only be available through the largest investment platforms, which are likely to have negotiated a better deal on charges because they sell so many of these funds.

Frustratingly, there is no consistency among the different fund groups in the abbreviations used for the various share classes.

As well as EQi’s Mutual Fund Selector, another way to select the correct share class is via sites such as FE Trustnet which, for each fund on the market, has one list for clean share classes only and one for other classes. The fund manager’s own website may also help.

However, you may still see at least four ‘clean’ share classes, at which point you may decide to just plump for the share class with the lowest charges.

EQi has also partnered with respected independent fund research company Square Mile Research to produce a Fund Select list that comprises funds that have passed its close scrutiny and could be the right choice for you whether you are just starting out, looking to build your portfolio or a seasoned investor.

Each fund is also rated according to its adherence to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria; see more about the selection process for EQis Fund Select list here.

If all else fails, you may wish to contact EQi’s Customer Experience Centre.

Alternatively, you may decide to swerve the entire conundrum, by finding the investment trust equivalent of the fund you are considering.

Investment trusts come in just one flavour, so you can’t pick the wrong one and there is likely to be one that, while not run in exactly the same way, is likely to perform similarly to a chosen fund.

Investment trusts differ from ordinary funds in that they are companies traded just like shares on the stock market; as a result the trust’s price will often diverge from that of its assets and trusts can also borrow in an attempt to make extra returns, but you should be able to find the investment exposure you require at your level of risk tolerance

To explore the differences between unit trusts and OEICs and investment trusts click here; to see Focus on Funds ezine click here.

September 2020

Read the latest edition of DIY Investor Magazine